Abolition is not new….

Time has come for abolitionist ideas and organising, but this movement is decades old. Abolitionists have been organising in different groups in the UK since the 1970’s.

In this section of the website we will be uploading archived issues of the magazine ‘The Abolitionist’. Detailing some of the history of abolitionist groups like Radical Alternatives to Prison and their campaigns, and highlighting some of those prominent in the movement.

If you would like to contribute material, archive material or your time to this aspect of the website please get in contact.

A history of Abolition in Britain

Campaigning against prisons and the police and attempting to build a just world, free of domination and an economy based on mutual cooperation are not new. There is a long history of organisations and individuals working towards these goals, even if all were not explicitly abolitionist. Abolitionist thinking has been influenced by the radical black tradition, indigenous organising, theological beliefs, marxist and anarchist ideas, queer and feminist analysis.

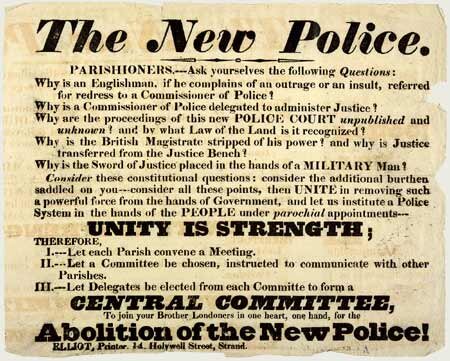

It is easy to forget just how recent both the police and the modern prison are. Both are innovations of the last two and a half centuries. They were introduced in Britain as mechanisms of class and colonial domination and their introduction was not uncontested.

Across the globe, in the many lands the British colonised, the imposition of criminal law, crucial in imposing racist regimes of exploitation, was resisted by indigenous and colonised people. These lands had established traditions for resolving conflicts often based on resolution and compensation – making good the harm – but these were replaced by British penal law based on blame, pain and racial domination. Many of the repressive techniques of policing we see today in Britain were developed by Britain’s racist colonial police.

Radical Alternatives to Prison (RAP)

RAP was originally founded in 1970 emerging out of the ashes of Prison Medical Reform Council (PMRC) which had been formed in 1943 to support conscientious objects and reactivated in the 1950s following the imprisonment of nuclear disarmament campaigners. At the PMRC’s last AGM Sandra Roszkowski and Ros Kane circulated a draft manifesto and from this initiative RAP was born. By 1972 RAP had a membership of 600 and it had attracted funding and an office base from Christian Action.

RAP had a significant ideological impact on the penal lobby in the 1970s. It’s clear message – that prisons could not rehabilitate and needed abolishing – represented a challenge to established penal reform groups like the Howard League. Whilst other groups had argued for a reduced use of prison and for reforming regimes RAP was clear, at least in its early days, that prison should be abolished. RAP was clear the issue was political. Prisons are linked to our unequal and unjust society. Prison abolition is part of a wider struggle.

By the end of the 1970s Christian Action got into financial difficulties and was forced to withdraw funding. RAP continued on limited funds and cease activity in the late 1980s. Its later years were characterised by debates over what to do with the dangerous few. There are clear lessons to contemporary abolitionists which we will be exploring over coming months.

Three specific initiatives of RAP deserve specific mention:

i. The Abolitionist

RAP set up its own journal The Abolitionist which ran from 1979 to 1987 (digital copies available here).

ii. Opposition to the redevelopment of Holloway Prison

RAP organised a campaign against the redevelopment of Holloway Prison. This included the publishing of the booklet Alternatives to Holloway.

iii. Newham Alternative Project

Set up in 1974 it sought to provide local courts with a non-coercive community-based alternative to imprisonment. This attempt to build alternatives was not unproblematic and again offers us lessons of developing our own strategies.

Preservation of the Rights of Prisoners and RAP

In 1972, between January and May there were over 50 peaceful demonstrations inside British Prisons. Out of these emerged the British prisoners’ union Preservation of the Rights of Prisoners (PROP), which was launched on the 11 May 1972 in the Prince Arthur pub opposite Pentonville prison in London with statements from a number of former prisoners. PROP had been formed to:

Preserve, protect, and to extend the rights of prisoners and ex-prisoners and to assist in their rehabilitation and re-integration into society, so as to bring about a reduction of crime.

PROP was concerned with the lives of prisoners and as such its focus was to demand immediate reforms rather than abolition. As such its relationship with RAP, which at this stage was uncompromisingly abolitionist was complex and sometimes difficult. There are lessons to be learnt from this relationship and in particular the dangers for abolitionist groups in not operating closely with prisoners and their families and friends. As we develop this history section, we will add an analysis of the relationship between RAP and PROP and the lesson for abolitionists today.

No More Prison/Communities of Resistance

In 2006 a new abolitionist group No More Prison was established by activists. Like RAP its focus was on prisons as set out in its founding statement:

Prisons are failed institutions that do not work. They are places of pain and social control and are brutal, abusive and damaging to everyone who is incarcerated in them. Prisons are fundamentally flawed and all attempts to reform them have failed. We are committed to their abolition by:

· Exposing the reality of imprisonment today;

· Stopping the building of new prisons and the expansion of existing prisons;

· Highlighting the fact that prisons not only fail prisoners but also have a negative impact on families and friends, victims and survivors and the whole community;

· Campaigning to close existing prisons;

· Opposing the criminalization of young people, working class and minority ethnic communities;

· Promoting radical alternatives to prison that focus on social and community welfare rather than punishment.

No More Prison brought together activists from a range of anti-prison groups as well as individuals. Its main activities were to support the campaigns of Pauline Campbell. Pauline, whose daughter died at the hands of the state in Styal Prison arranged a demonstration outside any prison where a woman died.

In 2008, Communities of Resistance (CoRe) also launched in response to plans announced by the UK government to build three new “titan” prisons (large scale prisons to hold 2,500 prisoners each). CoRe primarily focussed on stopping the Titan Prison project, opposing prison expansion and running workshops on abolitionist ideas. Although CoRE ceased organising shortly after the Titan prison plans were scrapped, out of CoRe emerged the Bent Bars Project, an LGBTQ prisoner solidarity / penpal scheme which continues to run today.

Reclaim Justice Network & Community Action on Prison Expansion

In 2012, the Reclaim Justice Network launched, as a collaboration of individuals, groups, campaigners, activists, trade unionists, practitioners and researchers and people most directly affected by criminal justice systems. RJN ran workshops, developed educational resources and engaged in campaigning work to ‘radically reduce the size, scope and reach of criminal justice systems.’ Campaigns included work to stop prison expansion, the reclaim holloway campaign and challenging private prison profiters like G4S.

Community Action on Prison Expansion (CAPE) was formed in 2014 to oppose the construction of Europe’s second largest prison, HMP Berwyn in North Wales. Since then CAPE has been actively leading on campaigns stop all forms of prison expansion, particularly in relation to the 2016 announcement of the Prison Estates Transformation Programme – a £1.3billion construction programme to create 10,000 new prison places in England & Wales.

In 2018, Reclaim Justice Network joined with a number of organisations to host the International Conference on Penal Abolition (ICOPA) in London. The conference theme was Abolitionist Futures: Building Social Justice, Not Criminal Justice. Participating groups included: Action for Trans Health; Bent Bars Project; Black Lives Matter UK; Empty Cages Collective; INQUEST; IWW London; Joint Enterprise Not Guilty by Association (JENGbA); London Campaign Against Police & State Violence; Netpol; North London Sisters Uncut; Race & Class collective; Reclaim Holloway; Smash IPP!; StopWatch; Women in Prison.

Abolitionist Futures as an organising group emerged from that conference.

Influence on British Abolitionists

Whilst abolitionists today often turn first to intellectuals from the United States like Ruth Wilson Gilmore and Angela Davis in the past British abolitionists have tended to look towards European thinkers such as Herman Bianchi, Nils Christie, Luc Hulsman, Thomas Mathiesen. RAP was also influenced by British pacifists, such as Fenner Brockway, whose critique of the prison was developed by their own imprisonment. Feminist antiviolence organisers in Britain also have a long history of engaging in mutual aid and direct community support to address violence outside systems of policing and prison. Abolitionist work in Britain has also been shaped by longstanding direct community resistance to policing and other forms of state violence.

Further Reading

Liz Dronfield, Outside Chance: The Story of the Newham Alternatives Project (London, 1980)

Elliott-Cooper A (2021) Black resistance to British policing. Black resistance to British policing. Manchester University Press

Mike Fitzgerald, Prisoners in Revolt (London, 1977)

Radical Alternatives to Prison, Alternatives to Holloway (London, 1972)

Vincenzo Ruggiero, Penal Abolitionism (Oxford, 2010)

Mick Ryan, The Acceptable Pressure Group: Inequality in the penal lobby: a case study of the Howard League and RAP (Farnborough, 1978)

Mick Ryan, The Politics of Penal Reform (London, 1983)

Mick Ryan and Joe Sim (2007) Campaigning for and campaigning against prisons: excavating and reaffirming the case for prison abolition. In: Jewkes Y (ed) Handbook on Prisons. Cullompton, Devon: Willan Publishing, pp.696-718.

Mick Ryan, ‘Prison Abolition in the UK: They Dare Not Speak Its Name?’ Social Justice 41 (3) pp. 107- 119 (2014)